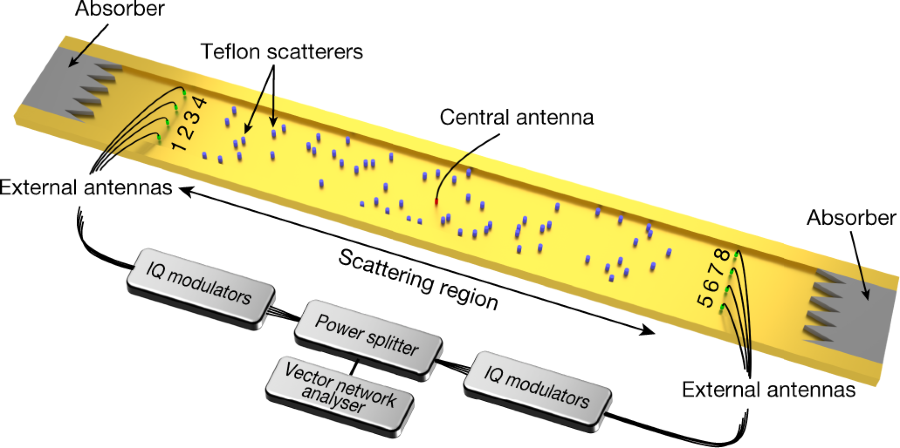

Experimental setup of the random anti-laser.

Scientists have found a way to build the ‘opposite’ of a laser – a device that absorbs a specific light wave perfectly. This can be done even in complicated systems, in which waves are scattered randomly, and has many technological applications.

At TU Wien (Vienna), a method has now been developed to make use of this effect, even in very complicated systems in which light waves are randomly scattered in all directions. The method was developed in Vienna with the help of computer simulations, and confirmed by experiments in cooperation with the University of Nice. This opens up new possibilities for all technical disciplines that have to do with wave phenomena. The new method has now been published in the journal Nature.

“Every day we are dealing with waves that are scattered in a complicated way – think about a mobile phone signal that is reflected several times before it reaches your cell phone,” says Prof. Stefan Rotter from the Institute for Theoretical Physics of the TU Vienna. “The so-called random lasers make use of this multiple scattering. Such exotic lasers have a complicated, random internal structure and radiate a very specific, individual light pattern when supplied with energy.”

With mathematical calculations and computer simulations, Rotter’s team could show that this process can also be reversed in time. Instead of a light source that emits a specific wave depending on its random inner structure, it is also possible to can build the perfect absorber, which completely dissipates one specific kind of wave, depending on its characteristic internal structure, without letting any part of it escape. This can be imagined like making a movie of a normal laser sending out laser light, and playing it in reverse.

“Because of this time-reversal analogy to a laser, this type of absorber is called an anti-laser,” says Stefan Rotter. “So far, such anti-lasers have only been realized in one-dimensional structures, which are hit by laser light from opposite sides. Our approach is much more general. We were able to show that even arbitrarily complicated structures in two or three dimensions can perfectly absorb a specially tailored wave. That way, the concept can be used for a wide range of applications.”

The main result of the research project: For every object that absorbs waves sufficiently strongly, a certain wave form can be found, which is perfectly absorbed by this object. “However, it would be wrong to imagine that the absorber just has to be made strong enough so that it simply swallows every incoming wave,” says Stefan Rotter. “Instead, there is a complex scattering process in which the incident wave splits into many partial waves, which then overlap and interfere with each other in such a way that none of the partial waves can get out at the end.” A weak absorber in the anti-laser is enough – for example a simple antenna taking in the energy of electromagnetic waves.

To test their calculations, the team worked together with the University of Nice. Kevin Pichler, the first author of the Nature publication, who is currently working on his dissertation in the team of Stefan Rotter, spent several weeks with Prof. Ulrich Kuhl at the University of Nice to put the theory into practice using microwave experiment. “Actually, it is a bit unusual for a theorist to perform the experiment,” says Kevin Pichler. “For me, however, it was particularly exciting to be able to work on all aspects of this project, from the theoretical concept to its implementation in the laboratory.”

The laboratory-built “Random Anti-Laser” consists of a microwave chamber with a central absorbing antenna, surrounded by randomly arranged Teflon cylinders. Similar to stones in a puddle of water, at which water waves are deflected and reflected, these cylinders can scatter microwaves and create a complicated wave pattern. “First we send microwaves from outside through the system and measure how exactly they come back,” explains Kevin Pichler. “Knowing this, the inner structure of the random device can be fully characterized. Then it is possible to calculate the wave that is completely swallowed by the central antenna at the right absorption strength. In fact, when implementing this protocol in the experiment, we find an absorption of approximately 99.8% of the incident signal.”

Anti-laser technology is still in its early stage, but it is easy to think of potential applications. “Imagine, for example, that you could adjust a cell phone signal exactly the right way, so that it is perfectly absorbed by the antenna in your cell phone,” says Stefan Rotter. “Also in medicine, we often deal with the task of transporting wave energy to a very specific point – such as shock waves shattering a kidney stone.” https://eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2019-03/vuot-tra030419.php https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-0971-3

Recent Comments