Discovery resolves longstanding question.

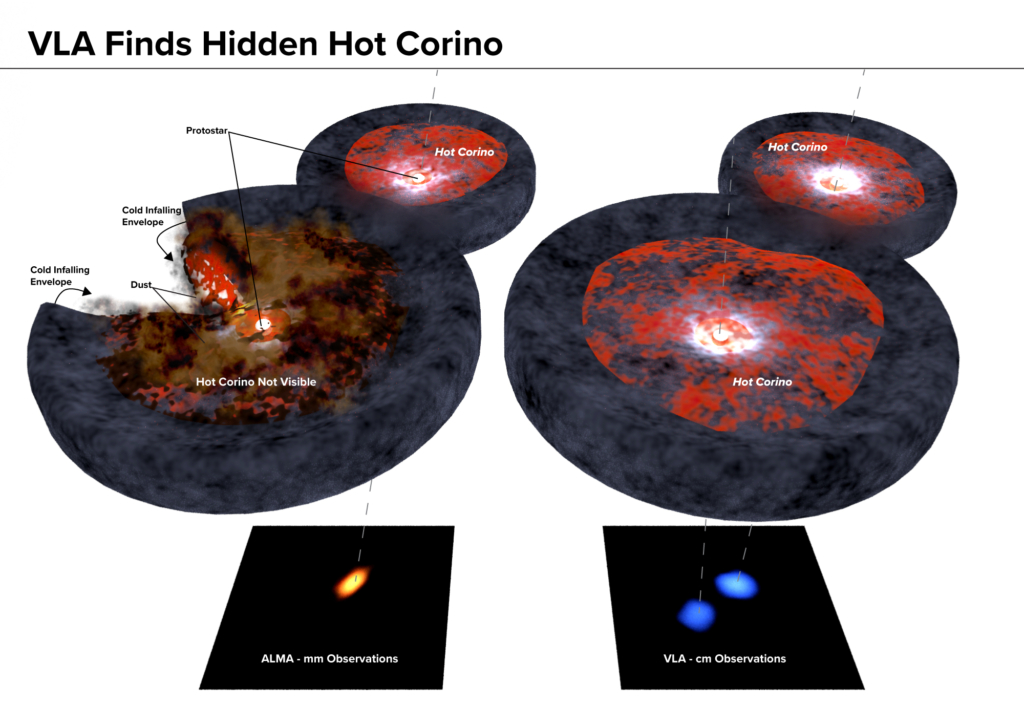

Some young, still-forming stars are surrounded by regions of complex organic molecules called ”hot corinos.” In some pairs of young stars forming together as binary pairs, astronomers found a hot corino around one, but not the other. Guessing that the unseen one might be obscured by dust, researchers studied such a pair with the VLA at radio wavelengths that readily pass through dust, and found the other one.

Astronomers acting on a hunch have likely resolved a mystery about young, still-forming stars and regions rich in organic molecules closely surrounding some of them. They used the National Science Foundation’s Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) to reveal one such region that previously had eluded detection, and that revelation answered a longstanding question.

The regions around the young protostars contain complex organic molecules that can further combine into prebiotic molecules that are the first steps on the road to life. The regions, dubbed “hot corinos” by astronomers, are typically about the size of our Solar System and are much warmer than their surroundings, though still quite cold by terrestrial standards.

The first hot corino was discovered in 2003, and only about a dozen have been found so far. Most of these are in binary systems, with two protostars forming simultaneously.

Astronomers have been puzzled by the fact that, in some of these binary systems, they found evidence for a hot corino around one of the protostars but not the other.

“Since the two stars are forming from the same molecular cloud and at the same time, it seemed strange that one would be surrounded by a dense region of complex organic molecules, and the other wouldn’t,” said Cecilia Ceccarelli, of the Institute for Planetary Sciences and Astrophysics at the University of Grenoble (IPAG) in France.

The complex organic molecules were found by detecting specific radio frequencies, called spectral lines, emitted by the molecules. Those characteristic radio frequencies serve as “fingerprints” to identify the chemicals. The astronomers noted that all the chemicals found in hot corinos had been found by detecting these “fingerprints” at radio frequencies corresponding to wavelengths of only a few millimeters.

“We know that dust blocks those wavelengths, so we decided to look for evidence of these chemicals at longer wavelengths that can easily pass through dust,” said Claire Chandler of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, and principal investigator on the project. “It struck us that dust might be what was preventing us from detecting the molecules in one of the twin protostars.”

The astronomers used the VLA to observe a pair of protostars called IRAS 4A, in a star-forming region about 1,000 light-years from Earth.They observed the pair at wavelengths of centimeters. At those wavelengths, they sought radio emissions from methanol, CH3OH (wood alcohol, not for drinking). This was a pair in which one protostar clearly had a hot corino and the other did not, as seen using the much shorter wavelengths.

The result confirmed their hunch.

“With the VLA, both protostars showed strong evidence of methanol surrounding them. This means that both protostars have hot corinos, and the reason we didn’t see the one at shorter wavelengths was because of dust,” said Marta de Simone, a graduate student at IPAG who led the data analysis for this object.

The astronomers caution that, while both hot corinos now are known to contain methanol, there still may be some chemical differences between them. That, they said, can be settled by looking for other molecules at wavelengths not obscured by dust.

“This result tells us that using centimeter radio wavelengths is necessary to properly study hot corinos,” Claudio Codella of Arcetri Astrophysical Observatory in Florence, Italy, said. “In the future, planned new telescopes such as the next-generation VLA and SKA, will be very important to understanding these objects.” https://public.nrao.edu/news/target-hiding-behind-dust/

Recent Comments