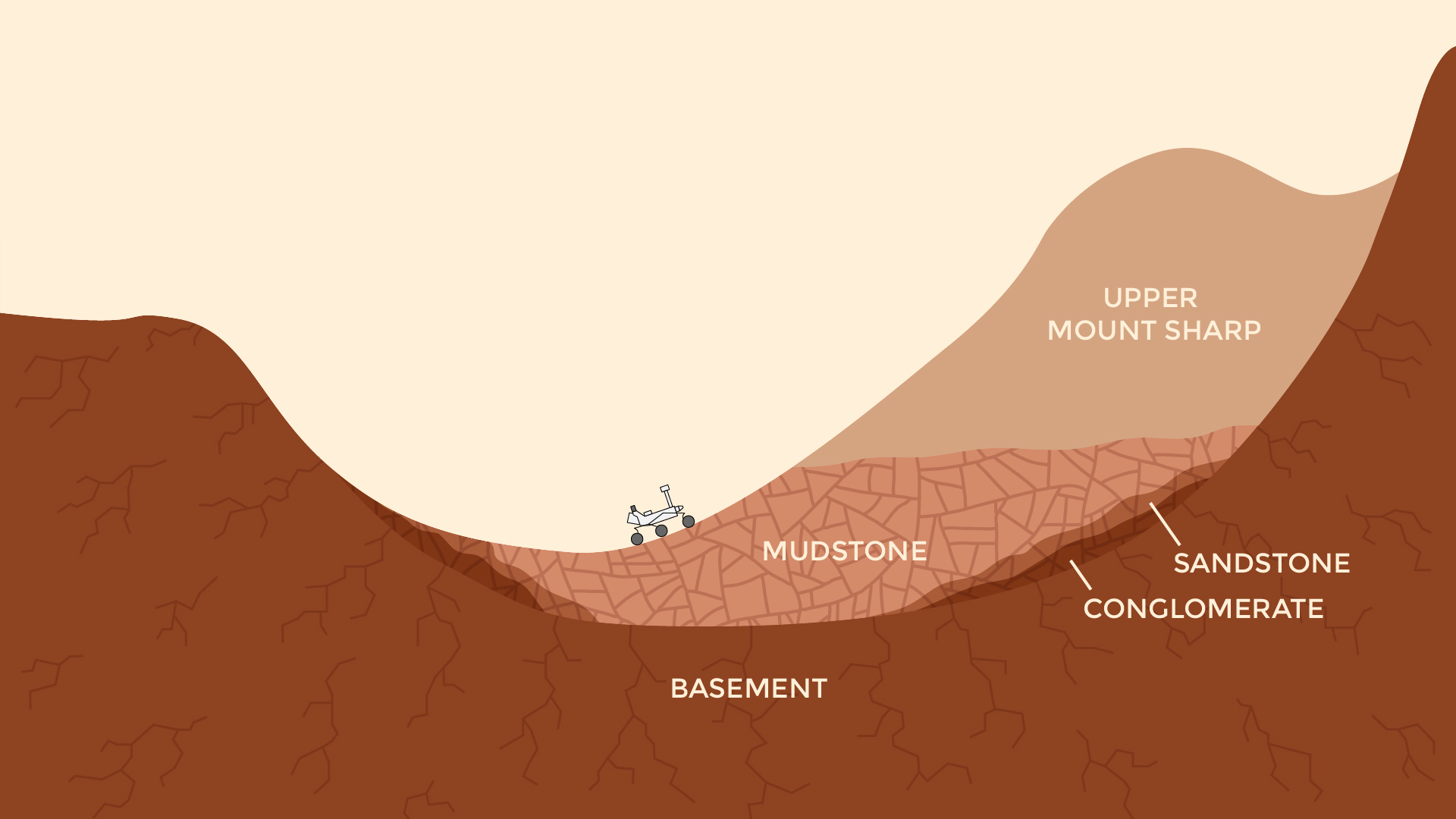

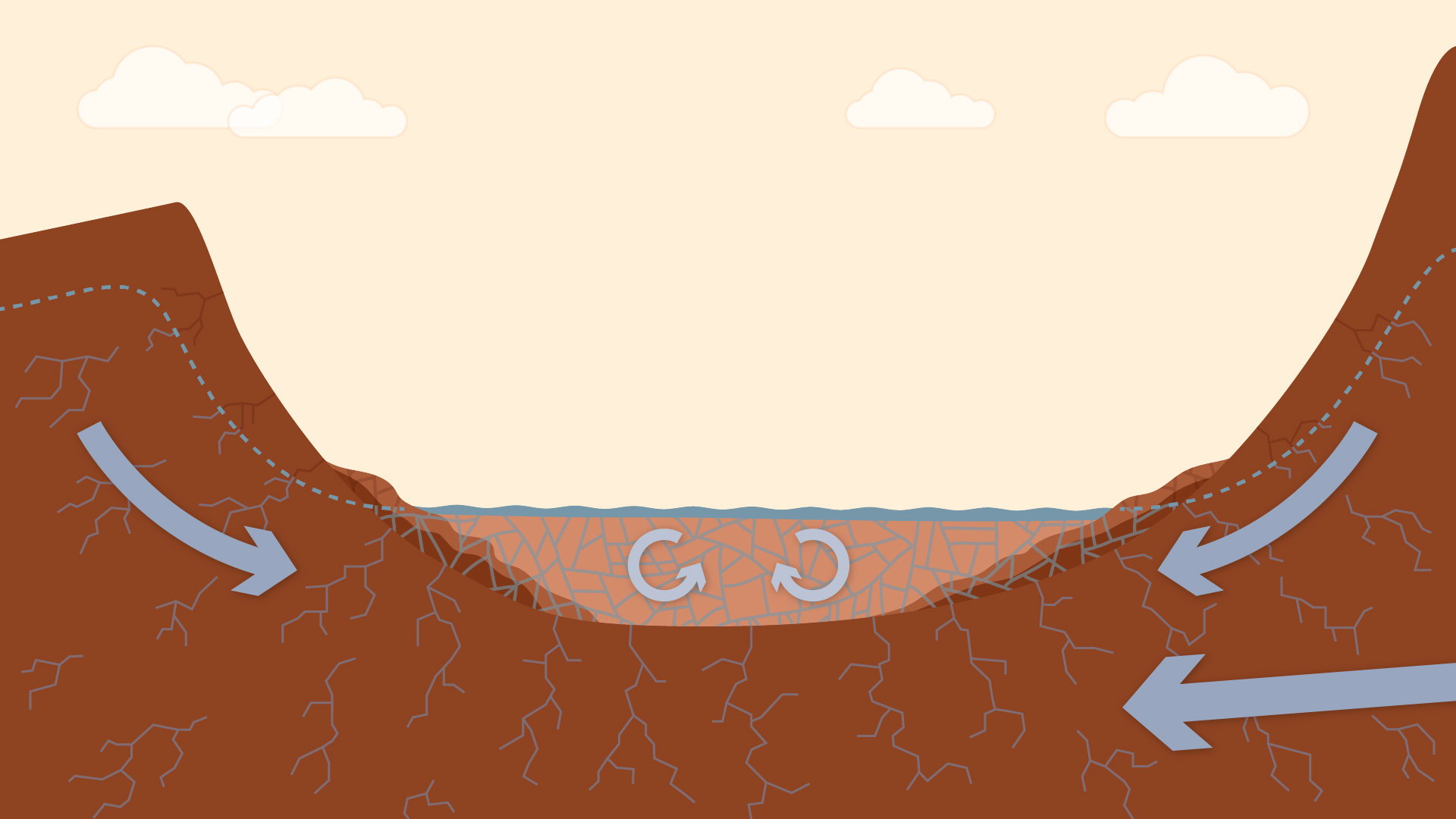

Images: This pair of drawings depicts the same location on Mars at two points in time: now and billions of years ago. The location is in Gale Crater, near the Red Planet’s equator. 1 shows a present-day snapshot of the northern half of Gale Crater. North is to the left. The underlying basement is the crust of Mars that forms the crater’s rim (left) and central peak (right). About 3.5 billion years ago, rivers brought sediment into the crater, depositing pebbles where the river was flowing more quickly, sand where the river entered a standing body of water in the center of the basin, and silt within this lake. Lake level rose over time as the sediments built up. Eventually they were buried by dry dust. These sediments later turned into the conglomerate, sandstone, mudstone, and duststone rocks that Curiosity has found. Wind then carved the stack of deposits into the present shape of a mountain, which Curiosity is climbing as approximately shown. The basement rock fractured during the initial impact that formed the crater, and the later sediments fractured as they were buried. 2 shows a snapshot in time when a lake was present in the crater. As on Earth, Martian lakes were the surface expression of a much larger lake and groundwater system. Spaces between grains and in fractures were saturated with water at levels below the water table (dashed blue line). This groundwater circulated due to gravity and the topography within and around the crater. In this case, groundwater pressurized under the nearby Martian highlands may have flowed into the crater, where it would be less confined. Groundwater also flowed downward from the lake. As the groundwater circulated, it drove chemical reactions that dissolved some minerals and precipitate others. Habitable environments in ancient Gale Crater – identified during Curiosity’s first year on Mars -expanded both in space and time beyond just the lakes. They extend throughout the subsurface where groundwater was present, and extended in time well after the lakes disappeared, when groundwater continued to circulate through the buried and fractured sediments.

NASA’s Curiosity rover is climbing a layered Martian mountain and finding evidence of how ancient lakes and wet underground environments changed, billions of years ago, creating more diverse chemical environments that affected their favorability for microbial life.

Hematite, clay minerals and boron are among the ingredients found to be more abundant in layers farther uphill, compared with lower, older layers examined earlier in the mission. Scientists are discussing what these and other variations tell about conditions under which sediments were initially deposited, and about how groundwater moving later through the accumulated layers altered and transported ingredients.

Effects of this groundwater movement are most evident in mineral veins. The veins formed where cracks in the layers were filled with chemicals that had been dissolved in groundwater. The water with its dissolved contents also interacted with the rock matrix surrounding the veins, altering the chemistry both in the rock and in the water.

“There is so much variability in the composition at different elevations, we’ve hit a jackpot,” said John Grotzinger, of Caltech in Pasadena, California, As the rover examines higher, younger layers, researchers are impressed by the complexity of the lake environments when clay-bearing sediments were being deposited, and also the complexity of the groundwater interactions after the sediments were buried.

“A sedimentary basin such as this is a chemical reactor,” Grotzinger said. “Elements get rearranged. New minerals form and old ones dissolve. Electrons get redistributed. On Earth, these reactions support life.”

Whether Martian life has ever existed is still unknown. No compelling evidence for it has been found. When Curiosity landed in Mars’ Gale Crater in 2012, the mission’s main goal was to determine whether the area ever offered an environment favorable for microbes.

The crater’s main appeal for scientists is geological layering exposed in the lower portion of its central mound, Mount Sharp. These exposures offer access to rocks that hold a record of environmental conditions from many stages of early Martian history, each layer younger than the one beneath it. The mission succeeded in its first year, finding that an ancient Martian lake environment had all the key chemical ingredients needed for life, plus chemical energy available for life. Now, the rover is climbing lower on Mount Sharp to investigate how ancient environmental conditions changed over time.

“We are well into the layers that were the main reason Gale Crater was chosen as the landing site,” said Curiosity Deputy Project Scientist Joy Crisp of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in Pasadena, California. “We are now using a strategy of drilling samples at regular intervals as the rover climbs Mount Sharp. Earlier we chose drilling targets based on each site’s special characteristics. Now that we’re driving continuously through the thick basal layer of the mountain, a series of drill holes will build a complete picture.”

Four recent drilling sites, from “Oudam” this past June through “Sebina” in October, are each spaced about 80 feet apart in elevation. This uphill pattern allows the science team to sample progressively younger layers that reveal Mount Sharp’s ancient environmental history.

One clue to changing ancient conditions is the mineral hematite. It has replaced less-oxidized magnetite as the dominant iron oxide in rocks Curiosity has drilled recently, compared with the site where Curiosity first found lakebed sediments. “Both samples are mudstone deposited at the bottom of a lake, but the hematite may suggest warmer conditions, or more interaction between the atmosphere and the sediments,” said Thomas Bristow of NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California. He helps operate the Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) laboratory instrument inside the rover, which identifies minerals in collected samples.

Chemical reactivity occurs on a gradient of chemical ingredients’ strength at donating or receiving electrons. Transfer of electrons due to this gradient can provide energy for life. An increase in hematite relative to magnetite indicates an environmental change in the direction of tugging electrons more strongly, causing a greater degree of oxidation in iron.

Another ingredient increasing in recent measurements by Curiosity is the element boron, which the rover’s laser-shooting Chemistry and Camera (ChemCam) instrument has been detecting within mineral veins that are mainly calcium sulfate. “No prior mission has detected boron on Mars,” said Patrick Gasda of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, New Mexico. “We’re seeing a sharp increase in boron in vein targets inspected in the past several months.” The instrument is quite sensitive; even at the increased level, boron makes up only about one-tenth of one percent of the rock composition.

Boron is famously associated with arid sites where much water has evaporated away — think of the borax that mule teams once hauled from Death Valley. However, environmental implications of the minor amount of boron found by Curiosity are less straightforward than for the increase in hematite.

Scientists are considering at least two possibilities for the source of boron that groundwater left in the veins. Perhaps evaporation of a lake formed a boron-containing deposit in an overlying layer, not yet reached by Curiosity, then water later re-dissolved the boron and carried it down through a fracture network into older layers, where it accumulated along with fracture-filling vein minerals. Or perhaps changes in the chemistry of clay-bearing deposits, such as evidenced by the increased hematite, affected how groundwater picked up and dropped off boron within the local sediments.

“Variations in these minerals and elements indicate a dynamic system,” Grotzinger said. “They interact with groundwater as well as surface water. The water influences the chemistry of the clays, but the composition of the water also changes. We are seeing chemical complexity indicating a long, interactive history with the water. The more complicated the chemistry is, the better it is for habitability. The boron, hematite and clay minerals underline the mobility of elements and electrons, and that is good for life.” http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=6700

Recent Comments