Nanosecond pulsed electric fields (nsPEFs) produce strong electrical effects by focusing a high powered electrical pulse over a very short period of time. They are attracting attention as a method of physically stimulating matter in various fields, particularly in the life sciences. Recently, researchers from Kumamoto University in Japan found that stimulating immune cells with nsPEFs can cause them to respond as if they were being stimulated by bacteria.

Researchers from the Institute of Pulsed Power Science (IPPS) selected a human leukemia cell line that is frequently used to study blood cell differentiation, the HL-60 cell line, to test the effects of nsPEFs on immune cells. First, they differentiated the cells into neutrophils, the most abundant type of white blood cell. Neutrophils play an important role in the immune system because they use phagocytosis, secretions of antimicrobial proteins, and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) to kill bacteria infecting the body. NETs are created from neutrophil DNA that is released from their nucleus. This then forms an extracellular fibrous network that entraps bacteria and increases the local concentration of antimicrobials.

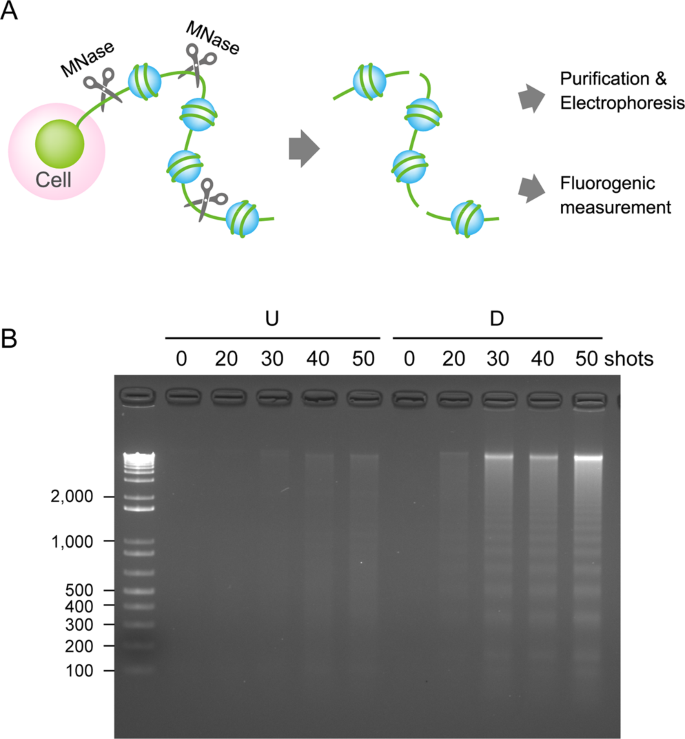

The researchers then analyzed neutrophil and undifferentiated HL-60 cell responses to nsPEF exposure where they observed chromosomal DNA being released from neutrophils, and a special modification reaction called citrullination occurring in histones. Since these reactions only occurred in the neutrophils, the researchers considered these cellular responses to be equivalent to the formation of NETs that form when neutrophils are stimulated by bacteria. In other words, they seem to have found a way to stimulate neutrophils using nsPEFs to cause an immune cell response to bacteria without actually using bacteria.

“Many studies have shown that nsPEFs are promising for cancer treatment applications,” said study leader, Professor Ken-ichi Yano from Kumamoto University’s IPPS. “Our research has shown that nsPEFs can also be used to stimulate cells to determine their function. We believe this has a wide range of potential biomedical applications.” https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-44817-9

Recent Comments