Protected surface states are akin to corner states of higher-order topological insulators. An international team of scientists has discovered an exotic new form of topological state in a large class of 3D semi-metallic crystals called Dirac semimetals. The researchers developed extensive mathematical machinery to bridge the gap between theoretical models with forms of ‘higher-order’ topology (topology that manifests only at the boundary of a boundary) and the physical behavior of electrons in real materials.

Fundamental research in condensed matter physics has driven tremendous advances in modern electronic capabilities. Transistors, optical fiber, LEDs, magnetic storage media, plasma displays, semi-conductors, superconductors – the list of technologies born of fundamental research in condensed matter physics is staggering. Scientists working in this field continue to explore and discover surprising novel phenomena that hold promise for tomorrow’s technological advances.

An important line of inquiry in this field involves topology – a mathematical framework for describing surface states that remain stable even when the material is deformed by stretching or twisting. The inherent stability of topological surface states has implications for a range of applications in electronics and spintronics.

Now, an international team of scientists has discovered an exotic new form of topological state in a large class of 3D semi-metallic crystals called Dirac semimetals. The researchers developed extensive mathematical machinery to bridge the gap between theoretical models with forms of “higher-order” topology (topology that manifests only at the boundary of a boundary) and the physical behavior of electrons in real materials.

The team comprises scientists at Princeton University, including postdoctoral researcher Dr. Benjamin Wieder, Chemistry Professor Leslie Schoop, and Physics Professor Andrei Bernevig; at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Physics Professor Barry Bradlyn; at the Institute of Physics Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, Physics Professor Zhijun Wang; at State University of New York at Stony Brook, Physics Professor Jennifer Cano (Cano is also affiliated with the Simons Foundation’s Flatiron Institute); and at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Physics Professor Xi Dai. The team’s results were published in the journal Nature Communications on January 31, 2020.

Over the past decade, Dirac and Weyl fermions have been predicted and experimentally confirmed in a number of solid-state materials, most notably in crystalline tantalum arsenide (TaAs), the first-discovered topological Weyl fermion semimetal. Several researchers observed that TaAs exhibits 2D topological surface states known as “Fermi arcs.” But similar phenomena observed in Dirac fermion semimetals have eluded understanding, until now.

What is a Fermi arc? In the context of semimetals, it’s a surface state behaving like one-half of a two-dimensional metal; the other half is found on a different surface.

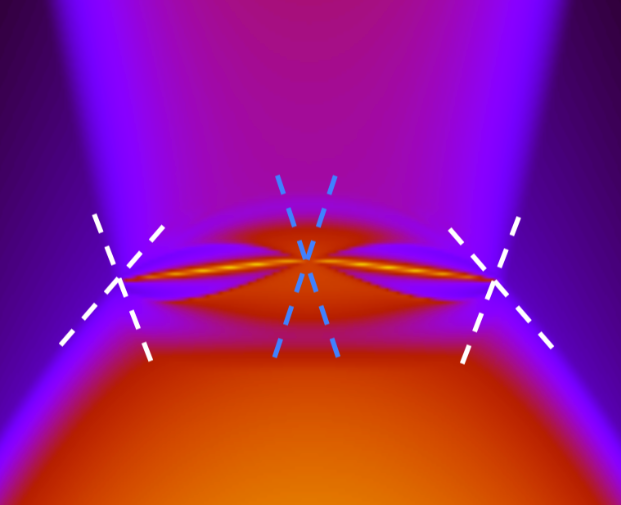

Bradlyn notes, “This is not something that’s possible in a purely 2D system, and can only happen as a function of the topological nature of a crystal. In this work, we found that the Fermi arcs are confined to the 1D hinges in Dirac semimetals.” In earlier work, Dai, Bernevig, and colleagues experimentally demonstrated that the 2D surfaces of Weyl semimetals must host Fermi arcs, regardless of the details of the surface, as a topological consequence of the Weyl points (fermions) present deep within the bulk of the crystal. This was first theoretically predicted by Vishwanath, et al.

“Weyl semimetals have layers like onions,” notes Dai. “It’s remarkable that you can keep peeling the surface of TaAs, but the arcs are always there.”

Researchers have also observed arc-like surface states in Dirac semimetals, but attempts to develop a similar mathematical relationship between such surface states and Dirac fermions in the bulk of the material have been unsuccessful: it was clear the Dirac surface states arise from a different, unrelated mechanism, and it was concluded the Dirac surface states were not topologically protected.

In the current study, the researchers were surprised to encounter Dirac fermions that appeared to exhibit topologically protected surface states, contradicting this conclusion. Working on models of Dirac semimetals derived from topological quadrupole insulators – higher-order topological systems recently discovered by Bernevig in collaboration with Illinois Physics Professor Taylor Hughes — they found that this new class of materials exhibits robust, conducting electronic states in 1D, or two fewer dimensions than the bulk 3D Dirac points.

Initially confounded by the mechanism through which these “hinge” states appeared, the researchers worked to develop an extensive, exactly solvable model for the bound states of topological quadrupoles and Dirac semimetals. The researchers found that, in Dirac semimetals, Fermi arcs are generated by a different mechanism than the arcs in Weyl semimetals.

“In addition to settling the decades-old problem of whether condensed matter Dirac fermions have topological surface states,” Wieder notes, “we demonstrated that Dirac semimetals represent one of the first-solid state materials hosting signatures of topological quadrupoles.”

Bradlyn adds, “Unlike Weyl semimetals, whose surface states are cousins of the surfaces of topological insulators, we have shown that Dirac semimetals can host surface states that are cousins of the corner states of higher-order topological insulators.”

Bradlyn describes the team’s methodology: “We took a three pronged approach to sort things out. First, we constructed some toy models for systems that we expected to have these properties, inspired by previous work on higher-order topological systems in 2D, and using group theory to enforce constraints in three dimensions. This was done primarily by Dr. Wieder, Prof. Cano, and myself.

“Second, Dr. Wieder and I carried out a more abstract theoretical analysis of systems in two dimensions, deriving the conditions for which they are required to exhibit hinge states, even outside of toy models.”

“Third, we performed an analysis of known materials, combining Professor Leslie Schoop’s chemistry intuition, our symmetry constraints, and ab initio calculations from Professor Zhijun Wang to show that our hinge arc states should be visible in real materials.”

When the dust settled, the team found that almost all condensed matter Dirac semimetals should in fact exhibit hinge states. “Our work provides a physically observable signature of the topological nature of Dirac fermions, which was previously ambiguous,” notes Cano.

Bradlyn adds, “It’s clear that numerous previously studied Dirac semimetals actually do have topological boundary states, if one looks in the right place.”

Through first-principles calculations, the researchers theoretically demonstrated the existence of overlooked hinge states on the edges of known Dirac semimetals, including the prototypical material, cadmium arsenide (Cd3As2).

Bernevig comments, “With an amazing team combining skills from theoretical physics, first-principles calculations, and chemistry, we were able to demonstrate the connection between higher-order topology in two dimensions and Dirac semimetals in three dimensions, for the first time.”

The team’s findings have implications for the development of new technologies, including in spintronics, because the hinge states can be converted into edge states whose direction of propagation is tied to their spin, much like the edge states of a 2D topological insulator. Additionally, nanorods of higher-order topological semimetals could realize topological superconductivity on their surfaces when proximitized with conventional superconductors, potentially realizing multiple Majorana fermions, which have been proposed as ingredients for achieving fault-tolerant quantum computation. https://physics.illinois.edu/news/article/36128

Recent Comments