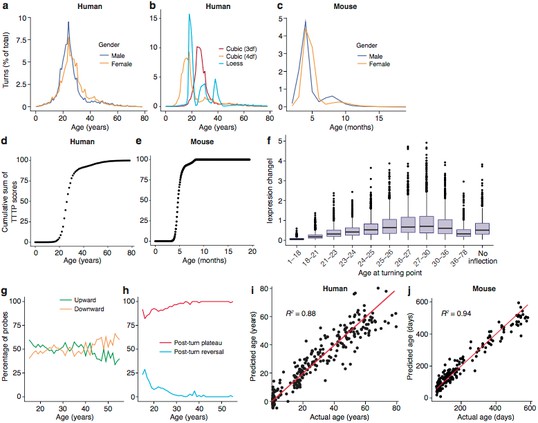

Trajectories and turning points characterise brain age. (a) Percentage of TTTPs at each age of human lifespan. Mean age is 26.0 years for males and 27.5 years for females. (b) Percentage of TTTPs at each age of human lifespan using three different methods for fitting splines. Mean age is 31.3 years using cubic splines with 3 degrees of freedom, 21.6 years using cubic splines with 4 degrees of freedom and 25.2 years using Loess regression. (c) Percentage of TTTPs at each age of mouse. Mean age is 156 days for males and 165 days for females. (d) Cumulative sum of TTTP scores for every year of life in the Braincloud dataset. (e) Cumulative sum of TTTP scores for every year of life in the mouse hippocampus dataset. (f) The TTTPs for genes with the greatest expression changes prior to the TTTP (ΔE) were concentrated around the late-twenties. (g) Percentage of probes associated with TTTPs that up- or down-regulate prior to turning. (h) Percentage of probes with TTTPs which plateau or reverse after turning. (i) and (j). Age of individual mice and humans can be accurately predicted using a Support Vector Machine trained on the expression data. Individual points represent each mRNA sample.

Brain scientists have identified a genetic programme that controls the way our brain changes throughout life. The programme controls how and when brain genes are expressed at different times in a person’s life to perform a range of functions. Experts say the timing is so precise that they can tell the age of a person by looking at the genes that are expressed in a sample of brain tissue.

Scientists analysed existing data which measured gene expression in brain tissue samples from across the human lifespan – from development in the womb up to 78 years of age. They found the timing of when different genes are expressed follows a strict pattern across the lifespan. Most of the changes in gene expression in the brain were completed by middle-age, the study found. The gene programme is delayed slightly in women compared with men, suggesting that the female brain ages more slowly than the male.

The biggest reorganisation of genes occurs during young adulthood, peaking around age 26. These changes affected the same genes that are associated with schizophrenia. The team says this could explain why people with schizophrenia do not show symptoms until young adulthood, even though the genetic changes responsible for the condition are present from birth.

The study found the genetic programme is present in mice too, although it changes more rapidly across their shorter lifespan. This suggests that the calendar of brain aging is shared between all mammals and may be millions of years old. Researchers next plan to study how the genetic programme is controlled, which could lead to therapies that alter the course of brain aging. It could also hold clues to new treatments for schizophrenia and other mental health problems in young adults.

Professor Seth Grant, Head of the Genes to Cognition Laboratory at the University of Edinburgh, said: “The discovery of this genetic programme opens up a completely new way to understand behaviour and brain diseases throughout life.” Dr Nathan Skene, Research Scientist at the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, said: “Many people believe our brain simply wears out as we age. But our study suggests that brain aging is strictly controlled by our genes.” https://elifesciences.org/articles/17915 https://eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-09/uoe-sdg091117.php

Recent Comments