This Microscopic Image Mosaic is the “smoking gun” for this story (the aqueous alteration part, not the acid fog). It shows a pre-existing crack which is being “healed over”, which is evidence for the gel weathering alteration process. This image is from a Watchtower Class outcrop named Hillary on the Husband Hill summit. The full mosaic shown on the left is ~5 cm across. Credit: Image courtesy NASA/JPL and S. Cole.

While Mars doesn’t have much in the way of Earth-like weather, it does evidently share one kind of weird meteorology: acid fog.

Planetary scientist Shoshanna Cole has pieced together a compelling story about how acidic vapors may have eaten at the rocks in a 100-acre area on . She used a variety of data gathered by multiple instruments on the 2003 Mars Exploration Rover Spirit to tease out information from exposures of the ancient bedrock.

The work focused on the ‘Watchtower Class’ outcrops on Cumberland Ridge and the Husband Hill summit. “The special thing about Watchtower Class is that it’s very widespread and we see it in different locations. As far as we can tell, it’s part of the ground there,” which means that these rocks record environments that existed on Mars billions of years ago. Spirit examined Watchtower Class rocks at a dozen locations spanning about 200 meters along Cumberland Ridge and the Husband Hill summit. The chemical composition of these rocks, as determined by Spirit’s Alpha Proton X-ray Spectrometer (APXS), is the same, but the rocks looked different to all of the other instruments.

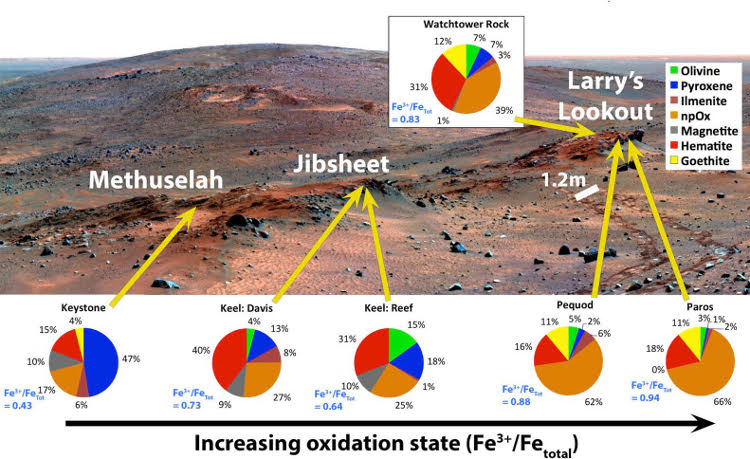

Across Cumberland Ridge the Mössbauer Spectrometer showed there was a surprisingly wide range in the proportion of oxidized to total iron, as if something had reacted with the iron in these rocks to different degrees. This iron oxidation state ranges from 0.43 to 0.94 across a span of only 30 meters. Meanwhile, data from both Mössbauer Spectrometer and the Miniature Thermal Emission Spectrometer (Mini-TES) showed that the minerals within the rocks changed and lost their structure, becoming less crystalline and more amorphous. And these trends match the size of small bumps, ie agglomerations, seen in Pancam and Microscopic Imager pictures of the rocks. “So we can see the agglomerations progress in size from west to east and the iron changes in the same way,” Cole said. “It was super cool.”

False-color mosaic of Cumberland Ridge, with superimposed pie charts representing iron-bearing mineralogy. You don’t need to know anything about iron geochemistry to know that the stuff represented by the pie charts varies greatly across this scene, which is about 1/3 the size of a football field. Also, the 1.2 m scale bar is the distance between the rover’s right and left wheel track. Image from S. Cole, PhD thesis; background image: NASA/JPL/Cornell/Arizona State University; Moessbauer values from Morris et al. 2008 (doi: 10.1029/2008JE003201).

But the fact that the rocks were otherwise the same in composition indicates that they were originally identical. “…something happened to make them different from each other.”

Cole hypothesizes that the rocks were exposed to acidic water vapor from volcanic eruptions, similar to the corrosive volcanic smog, or “vog,” that poses health hazards in Hawaii from the eruptions of Kilauea. When the Martian vog landed on the surface of the rocks it dissolved some minerals, forming a gel. Then the water evaporated, leaving behind a cementing agent that resulted in the agglomerations. “There’s even one place where you see the cementing agent healing a fracture”

More support of this idea comes from a 2004 study where lab experiments exposing mock martian basalt rocks to sulfuric and hydrochloric acids. The results indicated that as these rocks are exposed to acids, they lose their crystalline structure.

Why the rock changes? Microclimates: similar to those in different areas of your home garden. The time that the gel was present on the rocks depended on how much sunshine and wind the rocks got. The more altered rocks, which have larger agglomerations, are on very steep slopes facing away from the Sun, which makes them shadier. The least altered rocks are on sunnier and gentler slopes, according to Cole.

Piecing together this Martian vog puzzle underscores the story of Spirit’s success.

“Spirit’s the rover who always had to try harder,” she said. “She was sent to Gusev Crater to look for lake deposits, but landed in lava field. She had to make a long trek to the Columbia Hills to find evidence of ancient watery environments. There’s still tons of data to analyze there, and that’s really nifty.”

http://www.geosociety.org/news/pr/2015/15-82.htm

Recent Comments