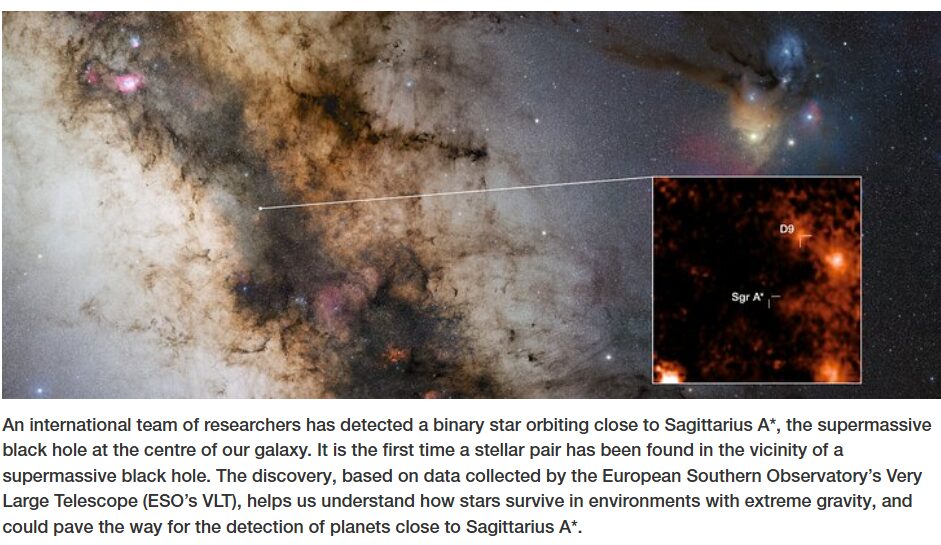

An international team of researchers has detected a binary star orbiting close to Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy. It is the first time a stellar pair has been found in the vicinity of a supermassive black hole.

The discovery, based on data collected by the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (ESO’s VLT), helps us understand how stars survive in environments with extreme gravity, and could pave the way for the detection of planets close to Sagittarius A*.

“Black holes are not as destructive as we thought,” says Florian Peißker, a researcher at the University of Cologne, Germany, and lead author of the study published in Nature Communications.

Binary stars, pairs of stars orbiting each other, are very common in the universe, but they had never before been found near a supermassive black hole, where the intense gravity can make stellar systems unstable.

This new discovery shows that some binaries can briefly thrive, even under destructive conditions. D9, as the newly discovered binary star is called, was detected just in time: it is estimated to be only 2.7 million years old, and the strong gravitational force of the nearby black hole will probably cause it to merge into a single star within just one million years, a very narrow timespan for such a young system.

“This provides only a brief window on cosmic timescales to observe such a binary system—and we succeeded,” explains co-author Emma Bordier, a researcher also at the University of Cologne and a former student at ESO.

For many years, scientists also thought that the extreme environment near a supermassive black hole prevented new stars from forming there. Several young stars found in close proximity to Sagittarius A* have disproved this assumption. The discovery of the young binary star now shows that even stellar pairs have the potential to form in these harsh conditions.

“The D9 system shows clear signs of the presence of gas and dust around the stars, which suggests that it could be a very young stellar system that must have formed in the vicinity of the supermassive black hole,” explains co-author Michal Zajaček, a researcher at Masaryk University, Czechia, and the University of Cologne.

The newly discovered binary was found in a dense cluster of stars and other objects orbiting Sagittarius A*, called the S cluster. Most enigmatic in this cluster are the G objects, which behave like stars but look like clouds of gas and dust.

It was during their observations of these mysterious objects that the team found a surprising pattern in D9. The data obtained with the VLT’s ERIS instrument, combined with archival data from the SINFONI instrument, revealed recurring variations in the velocity of the star, indicating D9 was actually two stars orbiting each other.

“I thought that my analysis was wrong,” Peißker says, “but the spectroscopic pattern covered about 15 years, and it was clear this detection is indeed the first binary observed in the S cluster.”

The results shed new light on what the mysterious G objects could be. The team proposes that they might actually be a combination of binary stars that have not yet merged and the leftover material from already merged stars.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights. Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs, innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

Both facilities will allow the team to carry out even more detailed observations of the Galactic center, revealing the nature of known objects and undoubtedly uncovering more binary stars and young systems.

“Our discovery lets us speculate about the presence of planets, since these are often formed around young stars. It seems plausible that the detection of planets in the Galactic center is just a matter of time,” concludes Peißker. https://www.eso.org/public/news/eso2418/

Recent Comments