Coiled carbon nanotube yarns, created at the University of Texas at Dallas and imaged here with a scanning electron microscope, generate electrical energy when stretched or twisted. Credit: University of Texas at Dallas

An international team led by scientists at The University of Texas at Dallas and Hanyang University in South Korea has developed high-tech yarns that generate electricity when they are stretched or twisted. In a study published in the Aug. 25 issue of the journal Science, researchers describe “twistron” yarns and their possible applications, such as harvesting energy from the motion of ocean waves or from temperature fluctuations. When sewn into a shirt, these yarns served as a self-powered breathing monitor.

“The easiest way to think of twistron harvesters is, you have a piece of yarn, you stretch it, and out comes electricity,” said Dr. Carter Haines, associate research professor in the Alan G. MacDiarmid NanoTech Institute at UT Dalla. The yarns are constructed from carbon nanotubes. The researchers first twist-spun the nanotubes into high-strength, lightweight yarns. To make the yarns highly elastic, they introduced so much twist that the yarns coiled like an over-twisted rubber band.

“Fundamentally, these yarns are supercapacitors,” said Dr. Na Li, a research scientist at the NanoTech Institute. “In a normal capacitor, you use energy – like from a battery – to add charges to the capacitor. But in our case, when you insert the carbon nanotube yarn into an electrolyte bath, the yarns are charged by the electrolyte itself. No external battery, or voltage, is needed.”

When a harvester yarn is twisted or stretched, the volume of the CNT yarn decreases, bringing the electric charges on the yarn closer together and increasing their energy. This increases the voltage associated with the charge stored in the yarn, enabling the harvesting of electricity. Stretching the coiled twistron yarns 30 times a second generated 250 watts per kilogram of peak electrical power when normalized to the harvester’s weight, said Dr. Ray Baughman, director of the NanoTech Institute.

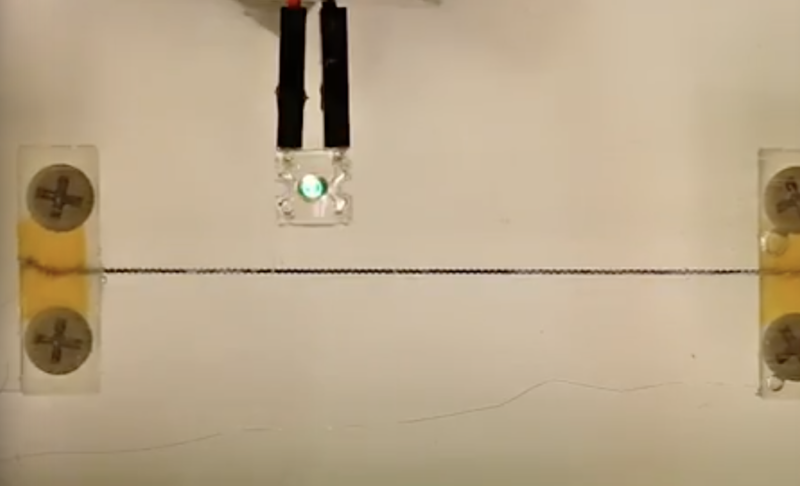

“Although numerous alternative harvesters have been investigated for many decades, no other reported harvester provides such high electrical power or energy output per cycle as ours for stretching rates between a few cycles per second and 600 cycles per second.” In the lab, the researchers showed that a twistron yarn weighing less than a housefly could power a small LED, which lit up each time the yarn was stretched.

When the yarn is stretched, the LED lights up.

To show that twistrons can harvest waste thermal energy from the environment, Li connected a twistron yarn to a polymer artificial muscle that contracts and expands when heated and cooled. The twistron harvester converted the mechanical energy generated by the polymer muscle to electrical energy. “There is a lot of interest in using waste energy to power the Internet of Things, such as arrays of distributed sensors,” Li said. “Twistron technology might be exploited for such applications where changing batteries is impractical.”

They also sewed twistron harvesters into a shirt. Normal breathing stretched the yarn and generated an electrical signal, demonstrating its potential as a self-powered respiration sensor. “Electronic textiles are of major commercial interest, but how are you going to power them?” Baughman said. “Harvesting electrical energy from human motion is one strategy for eliminating the need for batteries. Our yarns produced over a hundred times higher electrical power per weight when stretched compared to other weavable fibers reported in the literature.”

“In the lab we showed that our energy harvesters worked using a solution of table salt as the electrolyte,” said Baughman, who holds the Robert A. Welch Distinguished Chair in Chemistry in the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics. “But we wanted to show that they would also work in ocean water, which is chemically more complex.”

In a proof-of-concept demonstration, Dr. Shi Hyeong Kim waded into the frigid surf off the east coast of South Korea to deploy a coiled twistron in the sea. He attached a 10cm-long yarn, weighing only 1mg between a balloon and a sinker that rested on the seabed.Every time an ocean wave arrived, the balloon would rise, stretching the yarn up to 25%, thereby generating measured electricity.

Even though the investigators used very small amounts of twistron yarn in the current study, they have shown that harvester performance is scalable, both by increasing twistron diameter and by operating many yarns in parallel. “If our twistron harvesters could be made less expensively, they might ultimately be able to harvest the enormous amount of energy available from ocean waves,” Baughman said. “However, at present these harvesters are most suitable for powering sensors and sensor communications. Based on demonstrated average power output, just 31 milligrams of carbon nanotube yarn harvester could provide the electrical energy needed to transmit a 2-kilobyte packet of data over a 100-meter radius every 10 seconds for the Internet of Things.” http://www.utdallas.edu/news/2017/8/25-32663_No-Batteries-Required-Energy-Harvesting-Yarns-Gene_story-wide.html?WT.mc_id=NewsHomePageCenterColumn

Recent Comments