Researchers at The University of Texas at El Paso have successfully mapped specific regions in the brain that are activated in association with changes in blood sugar—also known as glucose—providing fundamental location information that could ultimately lead to more targeted therapies for people who struggle with conditions like diabetes.

The landmark 13-year study, published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine, describes how the team used careful microscopic analysis to pinpoint specific cell populations in the brain that appear responsive to rapid changes in blood sugar.

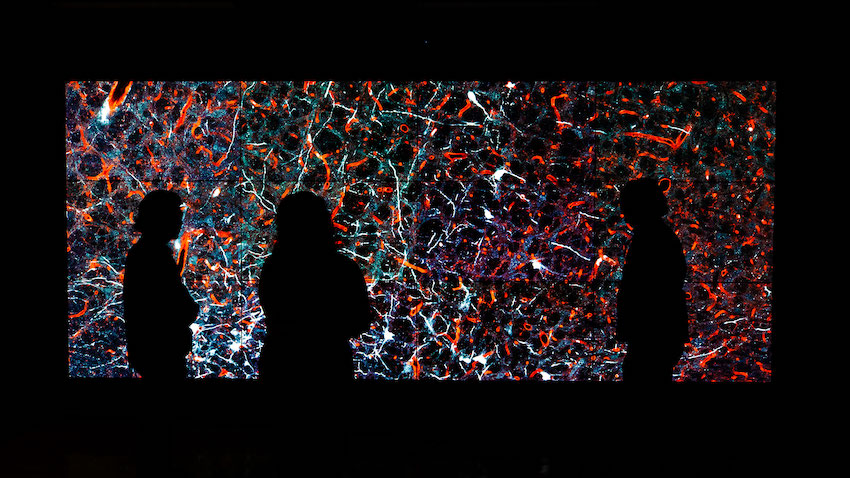

Arshad M. Khan, Ph.D., UTEP associate professor in biological sciences, and a team from his laboratory, led by doctoral student Geronimo Tapia, spent the past decade continuing work first performed by student researchers at the University of Southern California (USC), where Khan worked prior to joining the faculty at UTEP. Together with the help of two additional team members—UTEP Research Assistant Professor Sivasai Balivada, Ph.D., and USC’s Richard H. Thompson, Ph.D.—the team discovered what they believe may be glucose-sensitive cell populations in the brain and carefully mapped their locations in an open-access brain atlas.

The results of the study represent a significant step toward uniform global brain mapping and the evaluation of cellular responses to blood sugar in diabetic patients, Khan explained.

“I am grateful to all my contributors’ hard work throughout the years, both when I was at USC and now here at UTEP,” Khan said. “Finally knowing the exact coordinates for these structures in an open-access brain atlas means this spatial knowledge can now be utilized by the scientific community for the refined targeting of future clinical or therapeutic interventions for individuals experiencing blood sugar fluctuations and prediabetes.”

Khan added, “Finding these cells is a bit like monitoring the fuel sensors in a car when its fuel levels rise or fall. The next step will be to find the wiring that connects these sensors to other parts of the brain, a task for which we are already hard at work.”

Khan’s team was able to track blood sugar changes in responsive regions of the brain in 15 minutes, a process that previously took hours due to limitations in the biomarkers used to detect these changes.

The locus coeruleus (Latin for “blue place”)—a brain region so named because of its unique tissue color—produces norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter that plays an important role in arousal, attention and the body’s stress response. In the study, the locus coeruleus was found to be one of the few regions responsive early on during the blood sugar changes, suggesting it is an important arousal center for individuals with typeI and typeII diabetes when they experience life-threatening alterations in their blood sugar. Such alterations often occur when diabetics self-inject insulin, a hormone treatment which normalizes their high blood sugar levels, but which can also send them to dangerously low levels if incorrectly dosed.

The new knowledge of that region of the brain could ultimately help researchers monitor and intervene during the most dangerous effects of variations in blood sugar that arise as a common complication of diabetes management.

“This research is very important in our border region because there is a high prevalence of obesity and diabetes in our communities,” said Jessica Salcido Padilla, a UTEP graduate student from the Khan lab and study co-author. “Our goal is to identify exactly where certain processes happen in the brain so we can develop therapies, technologies or pharmaceuticals that help.”

“This important work by Dr. Khan and his team exemplifies our college’s—and our University’s—commitment to the advancement of discovery of public value,” said Robert Kirken, Ph.D., dean of the UTEP College of Science. “I sincerely congratulate them on the fruitful conclusion of their study, and I am hopeful and enthusiastic about the clinical therapies their findings will enable.” https://www.utep.edu/newsfeed/2023/researchers-map-the-brain-during-blood-sugar-changes.html:~:text=Researchers%20at%20UTEP%20have%20successfully,struggle%20with%20conditions%20like%20diabetes.

Recent Comments